For many, images of nuclear weapons testing blend seamlessly with the flat emptiness of the desert. That’s because much of the development and testing of these weapons occurred in the Southwest United States. In her new book Land of Nuclear Enchantment, author Lucie Genay examines the effects that this development has had on the state of New Mexico.

The U.S. development of nuclear weapons began in secret in places such as Los Alamos, New Mexico. After nuclear weapons were used to help the United States win WWII, Los Alamos and other areas of New Mexico were important locations for the continued development of the U.S. nuclear weapons program. However, this work did not occur in isolation from the people of New Mexico. The program had profound impacts on the state throughout the Cold War and beyond.

Los Alamos laboratory recently marked a 75-year anniversary and I posed some questions to Lucie Genay to discuss Land of Nuclear Enchantment and the many effects that the nuclear program has had on New Mexico.

How did you become interested in studying and writing on the subject of your book?

When I was a third-year student at university in France, I studied the Cold War in one of my US civilization classes and became fascinated with the topic. The fact that humanity had created weapons capable of destroying the planet several times over and that military strategists were able to devise policies based on this abstraction truly captivated me because it struck me as a way to address so many aspects of human nature. So when I decided to apply to study abroad as an exchange student for my first year in my Master’s program (my university had an exchange program with the University of New Mexico UNM) and I needed to choose a topic for my thesis, my advisor Dr. Susanne Berthier told me “do you know that the atomic bomb was designed and tested in New Mexico?”

I was even more excited to travel there and that is what first led me to researching the Manhattan Project and the scientists who had participated in it. I spent a year in the Land of Enchantment and fell in love with it. The courses that I remember the best were Gerald Vizenor’s on the Manhattan Project and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Dr. M.L. Garcia y Griego’s on the political history of the United States. I am profoundly indebted to both of them. The research I conducted for my thesis and the observations I made while living in NM shaped my approach to my PhD research thereafter. The book is adapted from my PhD dissertation.

What aspect of this subject does your book focus on?

The book focuses on the local perspective on the military-industrial complex that the US developed during World War 2 and the Cold War in the state of New Mexico. All the works I had read on nuclear weaponry mainly focused on the politicians, the scientists, and the military leaders, but did not talk much about the workers, the local residents, the anonymous partakers in the US atomic adventure. Also, little was said about the long-term impacts of the nuclear weapons industry.

Of course other authors have written about some aspects of the industry specifically (e.g. uranium mining, the environmental legacy of the Cold War in NM, the politics of opening of a nuclear waste repository near Carlsbad), but my approach was to try and assemble all of these elements in one book that would span the whole chronology of the nuclear weapons industry and the whole geography of the state, with a focus on the point of view of New Mexicans.

Another important aspect of the book is the analysis of New Mexico’s relation to the rest of the US through the concept of neocolonialism. Historians of the US West such as Gerald Nash have seen in World War 2 and the subsequent Cold War an opportunity for the West to emancipate itself from its quasi-colonial relationship with the industrialized East. I argue that although the development of a nuclear science-oriented sector brought dramatic socioeconomic and cultural changes to NM, the state’s dependence on eastern markets to sell raw materials transferred to a dependence on the federal government and the nuclear weapons industry. Thus, its fate remained tied to outside forces. More importantly, those who benefited the most from these changes, especially on the long-term, seemed to come from other states rather than be Native New Mexicans, so I see more continuity than rupture in this story in the end…

What are the major themes of this book?

Major themes in the book include social and economic history, ecology and environmental justice, nuclearism, federalism, colonialism and patriotism, ethnic discrimination, multiculturalism, mythologizing, and memory.

What resource materials did you use for your research?

My goal was to focus on testimonies from New Mexicans so I centered on collections of oral histories, a few of my own interviews, newspaper articles, unpublished research material (theses and dissertations) and any source in which I could find the perspective of local residents. Then I also used published material, official reports, and data to build the theoretical framework and the economic information I would need to develop my overall analysis.

What part of the research process was most enjoyable for you?

My research trips to New Mexico were definitely the best part. Talking to people about my work and seeing their interest in it, finding hidden gems in the archive centers, traveling around the state. I do not live in the US but in France, so it was always complicated in terms of time, money, and organization to plan a stay in NM to access the research material and meet with as many people as possible in a limited amount of time and on tight budget. These were very intense experiences. I have amazing friends there who also participated in making these trips very enjoyable.

What did you discover in your research that most surprised you?

Everything I learned about (sometimes consciously done) dangerous practices and contamination of the environment and people’s bodies shocked me. If I had to choose a surprise or something that caught my attention though, it would be the starting point of my research: seeing the discrepancy between the sophistication of the nuclear weapons industry, the wealth of a community like Los Alamos and the poverty of areas and populations juxtaposed to it. Los Alamos County is one of the richest counties in the US. NM is one of the poorest states. The US is known for being a land of extremes, including socioeconomically, and the way it is visible and accepted to some extent is always surprising to a French person, I suppose. I am not the first to mention this (and that is not to say that there is no inequality in France, of course) but I found it particularly striking in NM.

Was there anything you discovered that moved you?

I was moved by the connection many New Mexicans feel to their land and the genuine pain or nostalgia they expressed when talking about contamination of the environment or the loss of land-based traditions. Part of my family comes from a peasant background and I grew up eating the produce of my grandparents’ garden, so I think I could relate to that on some level.

They also talked about hard work and sacrifice for their children to have better, less difficult lives. The other side of my family is from a working class background, so they also passed down similar values to us. The sense of roots that New Mexicans have is very strong. It was deeply moving to learn about these family histories and see the struggles of younger generations who expressed how torn they were between tradition and economic necessity for example (what Vizenor calls “cultural schizophrenia”). Also, the observation that the most vulnerable, who rely on this land that they love, are the most likely to suffer from pollution is always very moving.

What was the most difficult issue to research?

Probably the most delicate subject was the divide between the town of Los Alamos and the valley. My fear was to be too intrusive or disrespectful when I went to talk to people in the Pueblos around Los Alamos. Finding testimonies of members of Native American communities was complicated. I was also concerned about being perceived as judgmental and as an outsider whenever I asked people questions. Remaining as objective as possible was important to me because my purpose was not to identify culprits and victims but to understand and explain how the nuclear weapons industry developed and what were the consequences of this development for local people. Some benefited from it; others were adversely impacted. For those people, on both sides, there are emotions, politics, and personal issues involved. You have to be respectful of that.

How much did the security and secrecy aspect of the facility affect community attitudes?

One chapter in the book deals in part with the paradoxes of Los Alamos, a town born in secrecy where people felt particularly safe because of the low unemployment, crime, and poverty rates combined with all the security measures connected to the presence of the national laboratories. Postwar Los Alamos residents considered their community an ideal place to raise children, despite the risks involved in living next to a laboratory that develops nuclear weapons and in an environment contaminated by radioactive substances.

Socioeconomic anxieties clearly superseded other concerns in this case. The impact of secrecy was too great throughout the state and over the period to summarize in a few sentences, but in this particular community, it was mostly visible through the sense of privilege that came with knowledge. Society was stratified based on educational attainment and degrees, i.e. how much people knew and what clearance level they could get based on that knowledge. Outside of this bubble, many were excluded because they did not have the degrees and the legitimacy; they were not trusted with any information presented as connected to national security, even though it could affect their communities, their environment, and their health.

Also, I understand the economic divide that exists but in what ways did the local community benefit from the presence of the facility?

New Mexicans benefited mainly because many were able to access employment close to their homes for the first time after the building of the laboratory and other facilities thereafter. Before World War 2, New Mexico was hardly industrialized and offered few opportunities to work for wages especially after the economic depression and drought of the 1930s, so most people supplemented their small agricultural revenues by becoming seasonal migrant workers who left the state to find employment elsewhere, as far as California. With the development of the nuclear weapons industry, thousands were hired locally, mainly on unskilled positions at first. The first generations benefited immensely, but the hiring and upward mobility both stalled with the following generations. Competition among job seekers became harsher. The labs hired skilled labor from other states and thus the inequality did not subside, on the contrary. This evolution is one of the core analyses in the book.

How much pride did local communities feel in the work being done? Did it give locals a feeling of being connected to the world in an international sense?

Patriotism is another aspect in the mechanism of industrial fatalism regarding defense-related industries. New Mexicans were and are proud of their participation in national security. Some among those who criticize the industry are afraid of being branded traitors or seen as unpatriotic. The same observations have been made by other researchers (such as Sarah Alisabeth Fox) who have studied the plight of downwinders, uranium miners, and atomic veterans. It took a long time for testimonies to resurface precisely because of this ambivalence between patriotic pride and bitter feelings of having been exploited or sacrificed in the name of national security. Be it at the labs or at the Pantex nuclear assembly facility on which I am currently working, employees express genuine pride in and enjoyment for what they do, but also a whole range of feelings from sadness and disillusionment to resentment and anger at what their occupations and the industry did or is doing to them.

In addition, did you come across any physical structures or items that intrigued you in some way?

I did, mostly at museums and tourist sites. I talk about memory in my conclusion because visiting the Trinity test site with its lava obelisk and the remains of the Jumbo cylinder, the museums where replicas of nuclear weapons and missiles are displayed, or the downtown area of Los Alamos with its homestead tour was a fascinating experience. Observing the attitude of other visitors was particularly interesting. In general, I think the memorialization of the Manhattan Project and of the nuclear era is a topic that deserves all our attention, since it shapes the way people will understand the birth and development of nuclear weapons as well as their impacts in the future.

What do you hope the book will do for readers?

My hope is that readers in New Mexico will learn something about their state, will find that my writing was faithful to their culture, and will be motivated to learn more about the nuclear weapons industry, potentially taking action to protect the environment, fight inequality and preserve cultural diversity. For readers outside of New Mexico, I hope they will be as delighted to discover this wonderful state and amazing people as I was. My approach to US history might surprise readers or even challenge them, but I hope they will be convinced by it and that other researchers will be inspired to continue the work on these crucial issues.

Did you have any difficulties in finishing the book and publishing it and if so, how did you overcome those?

Because this book is an adaptation of my PhD dissertation (which was over 500 pages), the main difficulty was to rework the text into a publishable manuscript that would not sound like a student’s work. I was very lucky that the Center for Southwest Research at UNM Zimmerman Library told me they would like a copy of my dissertation, and that UNM Press might be interested in publishing it, because I sent the first draft of my manuscript shortly after defending it and the Press was indeed interested, provided I made substantial changes. It was a long process, but I am grateful to the Press, to the editors, and to all those who helped me reshape this work and give it a real author’s rather than a student’s voice.

Do you have any online accounts where people can find more of your work?

I do not but the simplest way to find my work is to google my name. Some of my articles are available online. People will also find a list of my most recent publications on the resume available on the website of my research team. I try to update it regularly.

Author Biography

Lucie Genay

Associate Professor in US civilization 20th-21st centuries

University of Limoges, School of Humanities

Author of Land of Nuclear Enchantment: A New Mexican History of the Nuclear Weapons Industry, University of New Mexico Press, 2019.

More interviews: https://warscholar.org/posted-military-history-book-interviews/

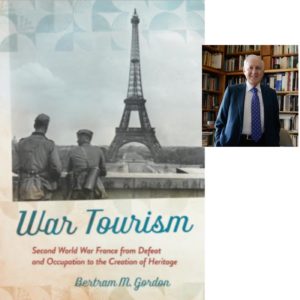

Dr. Bertram Gordon is a retired Professor of History. His specialty is modern France, especially the French Right and WWII. We spoke about his latest book on war tourism in France both during WWII and afterwards.

Dr. Bertram Gordon is a retired Professor of History. His specialty is modern France, especially the French Right and WWII. We spoke about his latest book on war tourism in France both during WWII and afterwards.