http://www.iupress.indiana.edu/product_info.php?products_id=809301

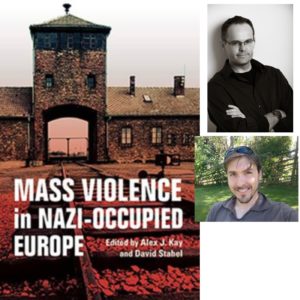

Nazi genocide was one of the most fearful and awful organized actions of the twentieth century. Their atrocities affected all of Europe and nations beyond. Though Nazi activities have been studied extensively, there is still much to learn. In their new book Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe, editors Alex J. Kay and David Stahel examine this subject with a series of essays.

Genocidal atrocities were committed all across Europe during WWII but despite the extensive research, there is still much that is unknown about these activities. How much did the war contribute to genocide? Was it part of German strategy or was it an outgrowth of the chaos of war? Who was involved and to what extent? Questions like these and others need more research and information to answer them.

Though Nazi genocide occurred decades ago, the repercussions of these events continue to affect global society. I posed some questions to Alex Kay and David Stahel about Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe

How did you become interested in studying and writing on the subject of your book?

David: The concept of “Mass Violence” in Nazi Occupied Europe is so shocking because of its ubiquity. To many non-specialists the assumption is we already know so much about the Nazi period, but in many instances the opposite is true. To give one example, in the 1990s the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum set out to document centres of Nazi persecution across Europe. So far, just three of the projected seven volumes have appeared, but it is the scale of their findings that is shocking. An estimated fifteen to twenty million people died or were imprisoned in these sites, which included ghettos, slave labour enterprises, transit camps, concentration camps and purpose-built killing centres like Auschwitz-Birkenau. When the research began in 2000, the research team, headed by Geoffrey P. Megargee, expected to locate and document some 7,000 sites based on post-war estimates. Yet, as the research continued, this number grew first to 11,500, then 20,000, then 30,000 and finally surpassed 40,000 to reach the current total of 42,500 sites.

Without question there is much still to learn, but more importantly, in an age of “fake news” the danger of Nazi criminality being disputed or minimalised is very real. The social media platform Facebook has been shown to have avoided removing Holocaust denial material in most of the Central European countries where it is illegal. A leaked company document stated that it did “not welcome local law that stands as an obstacle to an open and connected world”, meaning that moderators would only block Holocaust denial material if, “we face the risk of getting blocked in a country or a legal risk.”

Such developments underline the importance of continued research at the scholarly level, but also argues for a wider discussion and dissemination of historical research into the public sphere.

What aspect of this subject does your book focus on?

David: The aim of the book is to present research across the full spectrum of Nazi criminality – The Holocaust, Sinti and Roma, the Nazi concept of “Useless Eaters”, the Wehrmacht, Memorialization and Comparative History of genocide in the Second World War. Each of these categories includes research, which is based on leading research typically from non-English language publications. Indeed, the starting point for this book was a late night discussion in a Frankfurt pub about the number of significant studies that had never appeared in English.

What are the major themes of this book?

Alex: Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe argues for a more comprehensive understanding of what constitutes Nazi violence and who was affected by this violence. As David says, the individual contributions focus in particular on the Holocaust, the racial persecution of Europe’s Sinti and Roma, the eradication of those regarded by the Nazis as “useless eaters” (first and foremost psychiatric patients and Soviet prisoners of war), and the crimes of the Wehrmacht. The chapters featured also consider sexual violence, food depravation, and forced labor as aspects of Nazi aggression. The collection concludes with a consideration of memorialization and a comparison of Soviet and Nazi mass crimes.

A wider, overarching theme of the book is the predominance in the literature of works on individual Nazi atrocities or types of atrocity and the need, therefore, for us to examine Nazi policies of mass violence more collectively. Important and innovative recent works have taken a closer look at the relationship between the German conduct of the war in the years 1939 to 1945 and the unleashing of extreme mass violence by the National Socialist regime during this period, especially the key role played by food policy, supply, and shortages. However, research on the most systematic and comprehensive of the Nazi murder campaigns, the Holocaust, continues to be carried out in isolation from research on other strands of Nazi mass killing. The genocide of European Jewry was indeed unique in many ways, but it was nonetheless one part of a larger whole in the context of the war. A comprehensive, integrative history of Nazi mass killing, addressing not only the Holocaust but also the murder of psychiatric patients, the elimination of the Polish intelligentsia, the starvation of captured Red Army soldiers and the Soviet urban population, the genocide of the Roma, and the brutal anti-partisan operations, however, is yet to be written. This volume is not designed to fill that gap, but rather to provide an impetus for future research.

How coordinated were these Nazi actions? Was there simply a general policy of eradicating as many enemies as possible? How many Nazi leaders might have understood the level of killing that they were doing during the war?

Alex: For all the differences in the nature of the victims and, frequently, the ways in which they were murdered, they had something fundamental in common. It is no coincidence that virtually all of the more than twelve million victims of deliberate Nazi policies of mass murder were killed during the war years. The commonality shared by the different victim groups is closely related to the war. Each and every one of the victim groups was regarded by the Nazi regime in one way or another as a potential threat to Germany’s ability to fight and, ultimately, win a war for hegemony in Europe. This view was informed and justified by Nazi racial thinking, so that it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate German war strategy from Nazi genocidal racial policies. In fact, one might go so far as to argue that in the case of the German Reich genocide itself, and mass killing policies in general, constituted a war strategy. These were systematic killing programmes, and both the political and military leaderships were not only well aware of the scope of the killing but also deeply implicated in it.

How much did war operations overlap with mass violence against civilians or captured soldiers? Was it simply a situation where the military took territory and then civilian authorities conducted the mass violence or were military units also used to conduct mass violence against civilians or prisoners of war?

Alex: There was extensive overlap between mass violence against civilians and other non-combatants on the one hand and the military operations themselves on the other hand. As I said earlier, it is impossible to separate German war strategy from Nazi genocidal racial policies. The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw rightly pointed out many years ago that the Holocaust would not have been possible without the military victories and stubborn resistance of the Wehrmacht. This, however, is only half the story. In fact, it has long been known that numerous regular German army units actively participated in the mass shootings against Jews in the Soviet Union and in Serbia, either by providing shooters to the SS commandos or by carrying out massacres on their own initiative. In fact, the Wehrmacht participated directly in a number of mass killing programmes: the elimination of the Polish intelligentsia, the genocide of Serbian and Soviet Jewry, the starvation of captured Red Army soldiers and the Soviet urban population, and the brutal anti-partisan operations in Eastern Europe. Members of the Wehrmacht may even have constituted the majority of those responsible for mass crimes carried out on the part of the German Reich.

Do you find that people either in the past or present try to separate Nazi politics from the genocidal actions of Nazis during the war? That is, how often do you hear an argument such as “being a Nazi is a good thing as long as enemies are simply kept at bay by segregation or other non violent means rather than killing them.”

Alex: In the past, it was far more common for the supposed positives of Nazi politics – having enough to eat, full employment, law and order – to be emphasized and Nazi atrocities to be played down along the lines of “it was wartime” or “we didn’t know about it”. This kind of thing has now become increasingly rare and, indeed, taboo. Only neo-Nazis openly make such claims these days. To be honest, I don’t actually think I’ve ever heard anyone say “being a Nazi is a good thing”. Back in 2005, I attended a conference in Potsdam on Nazism, Communism, and the 20th Century, at which the historian Omer Bartov said that Stalinism did terrible things in achieving its goals, but with Nazism, the terrible things were the goals.

What part of the research process was most enjoyable for you?

David: Research is a process of discovery. I cannot speak for other authors in this book, but my own experience with Alex, both in producing this book and writing our chapter, was the model of scholastic collaboration. I see myself primarily as a military historian and my body of past works focus on operational and social histories of the Wehrmacht. This may seem an odd fit for this subject, but that would be a misconception.

Alex and I studied together for our respective PhDs at the Humboldt University in Berlin and being the only two non-Germans (as far as I am aware) in the history department at the time, we became fast friends. Both of us were working on the Nazi period, but Alex’s dissertation and subsequent research has always focused on the Nazi state and its criminality. Over 15 years of trading research notes and discussing respective projects we often commented on how often the same themes ran through our respective, but separate, fields of research. Perhaps that should not have surprised us, but one should not underestimate how much of a separation has existed between scholars that came before us. Much of the body of works that informed my early reading on the Wehrmacht’s history had almost no bearing on Alex’s literature and vice versa. The potential for collaboration was huge (although we are not the only ones have begun this work).

Our chapter is a reconceptualization of how we see the German soldier’s role in the war in the East and what standard we might use to understand and apply a label like “criminal”. The finer points of the argument I will leave for those interested in reading the chapter, but working with other scholars and making a contribution to such an important field of study is indeed both a process of discovery and an enjoyable one.

What did you discover in your research that most surprised you?

Alex: The exploitation of recent history for the purposes of nation-building and the construction of a cohesive national identity not only in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics, but also further west in Germany itself, demonstrates that the Nazi past remains very present, and hotly contested, throughout Europe. Thus, while European integration in a commercial, financial, and to some extent political respect may have progressed at a rapid pace over the last two decades or so, not least with the accession to the European Union and NATO of former Eastern Bloc states such as Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania, the very different historical experiences and memories mean that a common sense of European identity remains elusive.

In our attempts to reflect the view from Eastern Europe, too, it was helpful, therefore, to have several historians fluent in Eastern European languages on board, as well as one Russian historian who is a professor in Moscow and another contributor who is a professor in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius.

Was there anything you discovered that moved you?

Alex: Inevitably, working in this field, one does become somewhat desensitized over time to the numerous stories of violence and killing. If we didn’t, it would be impossible for us to do our work. Having said that, I’m still moved every time I read about the suffering of victims of Nazi atrocities. This empathy with our fellow human beings is something we should fight to retain, because once it’s gone, the floodgates to hatred, violence and death are wide open. For this reason, it’s vital to keep studying the perpetrators, as difficult as that might be. The mindset and conduct of someone who kills requires considerably more explanation than the mindset and conduct of someone who is killed. As the historian Timothy Snyder has noted, “It is less appealing, but morally more urgent, to understand the actions of the perpetrators. The moral danger, after all, is never that one might become a victim but that one might be a perpetrator or a bystander.”

What was the most difficult issue to research?

Alex: There’s no easy issue to research when looking at mass violence committed by Nazis or any other group. But the difficult topics are often the most important and sometimes the most rewarding.

What do you hope the book will do for readers?

David: There is no easy answer to a question like this. Most will use the book to inform an angle of their own research or as an overview to inform their teaching. They will typically be people familiar with the field and the events. While I hope they do find things of interest, my hope would be to gain at least a few reader from beyond this usual demographic (even if an edited collection of scholarly essays from a university press is never realistically going to have much popular appeal). The recent rise of populist political parties and politicians, who openly evoke previously unthinkable Nazi terminology and sometimes advocate variants on their policies, are supported by people who simply do not see these parallels. It is all very well for academics to write for the benefit of each other, but in the meantime, the real battle for historical truth may be lost. One must also look for ways to get beyond the usual audience and engage with the wider community. My university has promoted community engagement and we are increasingly being incentivised to engage beyond the confines of academia (perhaps here I should thank Cris Alvarez for such an opportunity). Whatever the benefit of this book I hope it contributes to a wider understanding of just what created, and allowed for, such widespread criminality.

What are your next research or writing projects?

Alex: I am under contract with Yale University Press to write a history of Nazi mass killing. It will look at the seven major killing programmes of deliberate mass murder between 1939 and 1945.

David: My next book is a fresh look at the German retreat from Moscow in 1941-1942 and will appear at the end of 2019 (see: Retreat from Moscow: A New History of Germany’s Winter Campaign, 1941-1942).

Dr David Stahel is an historian, author and Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales. He specialises in German military history of the Second World War.

Dr Alex J. Kay is Senior Lecturer at the University of Potsdam and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. His principal research interests are Nazi Germany, the Holocaust and comparative genocide.

More interviews: https://warscholar.org/posted-military-history-book-interviews/