Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Check out this book here https://amzn.to/2A73z3E

Check out this book here https://amzn.to/2A73z3E

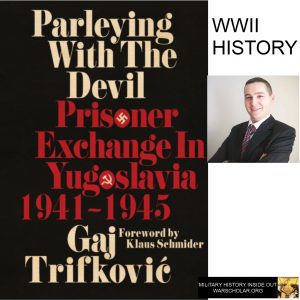

Gaj Trifkovic has had a lifelong interest in WWII especially as it relates to Yugoslavia. He earned his history degree in the subject and wrote his first book – a history of prisoner exchange in Yugoslavia during WWII. We spoke about the war in Yugoslavia, the book, and the process of getting published.

(THE AUDIO PLAYER IS AT THE BOTTOM OF THE POST.)

0:51 – Gaj talks about how he got into studying Yugoslavia in WWII.

4:10 – Gaj talks about the five main sections of the book starting with Serbia.

6:25 – Gaj talk about the military activities and situation in Yugoslavia during WWI.

8:31 – Gaj talks about the controversial March 1943 negotiations.

12:06 – Gaj talks about the Yugoslav neutral zone.

13:08 – Gaj talks about how much the German high command knew about this prisoner exchange.

14:11 – Gaj talks about how partisans dealt with prisoner exchanges.

16:33 – Gaj talks about what prisoners the Germans took.

17:52 – Gaj talks about how prisoners chosen for exchange were sometimes treated harshly.

19:46 – Gaj talks about local prisoner exchanges by units in the field.

21:00 – Gaj talks about non-German Axis prisoners.

22:20 – Gaj talks about prisoner exchanges in other historical contexts.

24:46 – Gaj talks about how Hitler was convinced to accept these exchanges.

26:06 – Gaj talks about whether the Germans exchanged “undesirables.”

27:04 – Gaj talks about the unwritten rules of prisoner exchange.

29:20 – Gaj talks about prisoner exchange closer to the end of the war.

32:35 – Gaj talks about large-scale execution of prisoners at the end of the war.

34:26 – Gaj talks about German and Axis prisoners in Yugoslavia at the end of the war.

38:58 – Gaj talks about post-war release of prisoners.

40:45 – Gaj talks about the archives and books he used for this research.

42:27 – Gaj talks about the self-censorship on both sides about prisoner exchange.

45:55 – Gaj goes into more detail about the neutral zone.

47:11 – We discuss what might be in the current location of the neutral zone.

51:32 – Gaj talks about how well the two sides got along in the neutral zone.

55:14 – Gaj talks about why he wrote the book in English rather than German.

57:38 – Gaj talks about how he tried to emulate “The Longest Day” in the writing of this book.

1:04:59 – Gaj can be found on researchgate.net and academia.edu.

Links of interest

https://www.kentuckypress.com/9781949668087/parleying-with-the-devil/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gaj_Trifkovic

https://independent.academia.edu/GajTrifkovic

For more “Military History Inside Out” please follow me at www.warscholar.org, on Facebook at warscholar, on twitter at Warscholar, on youtube at warscholar1945 and on Instagram @crisalvarezswarscholar. Or subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | Spotify

Guests: Gaj Trifkovic

Host: Cris Alvarez

Tags: military, history, military history, conflict, war, interview, non-fiction book, WWII, world war 2, Yugoslavia, Communist, Nazi, Fascism, Italy, Germany, Serbia, insurgency, Croatia, Wehrmacht, Montenegro, Tito, Sarajevo, Hitler, Macedonia, fascists, American Revolution, US Civil War, Slovenia, Luftwaffe, partisan, Austrians, secret police, British, The Longest Day, Global War Studies, world war two

Check out this book here https://amzn.to/2A73z3E

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.