https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/santos-granero-slavery-and-utopia

For many readers, the Amazon has been a place that brings up images of wild beauty, teeming wildlife, and violent death. It is a place considered pristine and uncivilized. Today the Amazon is seen as a vital environmental asset, the destruction of which is considered a harbinger of a fast approaching environmental disaster brought on by the unchecked growth of civilization.

But the Amazon’s struggle for survival is not a new one. Many indigenous peoples live in the Amazon and they have all had to deal with the encroachment of civilization. But these peoples didn’t simply succumb to the crush of development and exploitation. Some of them fought back and fought back successfully.

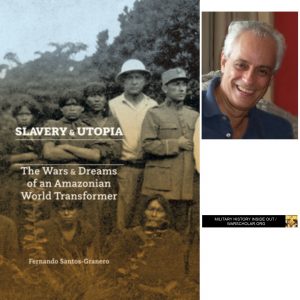

Fernando Santos-Granero has written about one such Amazonian leader and I spoke with him about his book Slavery and Utopia and the struggles of one man and his followers to save his people’s place in the Amazon.

How did you become interested in studying and writing on the subject of your book?

I became interested in the figure of Ashaninka Chief José Carlos Amaringo Chico by sheer chance. In 2008, Łukasz Krokoszyński, a young colleague, told me about a book published by Mieczysław B. Lepecki, a Polish Army officer, recounting his experiences during a 1928 reconnaissance trip to the Upper Ucayali River in Peruvian Amazonia.

What led Łukasz to bring this particular book to my attention was Lepecki’s mention of an encounter with an Ashaninka chief who claimed to be “son of the Sun.” His followers, according to Lepecki, called him Tasorentsi, the Ashaninka term for a category of gods, good spirits and divine emissaries that may be translated as “all-powerful blower world transformer.” Lepecki described Tasorentsi as a great chief and paramount leader of a violent uprising that in 1915 had swept the Upper Ucayali and Lower Urubamba, killing many rubber extractors and forcing the survivors to abandon the region.

Knowing of my interest in the struggles of the indigenous peoples of the Selva Central region against white people’s encroachment, Łukasz assumed that Lepecki’s reference would be of interest to me. I responded that I had never heard of an indigenous uprising on the Upper Ucayali at that date. And added that Lepecki was probably merging accounts of the well-recorded 1912-14 Ashaninka revolt in the neighboring Pichis, Perené and Pangoa river basins with older narratives about Juan Santos Atahualpa, head of an eighteenth-century millenarian and anticolonial uprising against the Spanish, who also styled himself “son of the Sun.” However, since I was not prepared to dismiss the story entirely, I embarked on a search for independent evidence confirming Lepecki’s information. An examination of the national and regional newspapers of the time confirmed not only that the uprising had taken place but also that Chief Tasorentsi had played a key role in its planning and execution.

What aspect of this subject does your book focus on?

At the beginning, I intended to focus my study on the 1915 Upper Ucayali uprising. The revolt coincided with the collapse of the rubber boom –the rapid economic prosperity derived from the extraction of natural rubber throughout Amazonia– and I was interested to determine whether it had been an isolated incident or an expression of a much wider indigenous discontent. However, as the information started piling up, and I realized that Chief Tasorentsi had played a crucial role in most of the social and political events that affected Ashaninka people during the first half of the twentieth century, I gradually changed the focus of my study to reconstructing the life and political trajectory of this extraordinary man.

What are the major themes of this book?

The reconstruction of Chief Tasorentsi’s political trajectory serves as a backdrop to examine three broader topics. Firstly, the tensions and conflicts between the indigenous peoples of the Selva Central region and the local representatives of the national society –rubber extractors, river traders, merchant houses, shippers and local authorities– during a chaotic and violent period Peruvian Amazon history. In second place, the strategies developed by indigenous leaders to liberate their peoples from white-mestizo oppressors, many of whom were involved in the enslavement and traffic of indigenous people; strategies that oscillated between armed confrontation and millenarian action going through calls for retreat and isolationism. Finally, the debates that the conflicts between white and indigenous peoples generated at the regional and national level opposing those who defended indigenous rights to their lands and lifeways to those who proposed their cultural assimilation and/or extermination.

What resource materials did you use for your research?

The book combines a vast array of materials: archival documents from national and regional repositories with oral histories recorded from knowledgeable indigenous elders; journalistic articles and editorials with field materials collected by Ashaninka specialists in the 1960s, 70s and 80s; Adventist and Catholic missionary literature with ethnographic works; articles produced by scientists and explorers with travelogues published by globetrotters and adventurers; dictionaries of indigenous languages with old maps, sky charts and atlases; and musical recordings and scores with photographs, early films and other visual materials. It is thus a work of historical anthropology; a hybrid book combining the conventions of anthropology and history.

What part of the research process was most enjoyable for you?

I especially enjoyed the archival work. In comparison to Andean indigenous peoples, native Amazonian peoples have received very little attention from colonial or post-colonial authorities. As a result, there are not many archival documents dealing with their history. When I began my research, I did not expect to find much in the way of written documents. I was thus quite surprised when I began to find documents that dealt directly with Chief Tasorentsi and his actions throughout the years. Even more enjoyable, however, was the process of slowly putting together the puzzle of Chief Tasorentsi’s life based on such disparate kinds of information.

What did you discover in your research that most surprised you?

My greatest discovery was the resourcefulness and versatility of indigenous leaders such as Chief Tasorentsi, who had the capacity to change and constantly re-invent himself in response to the challenges posed by changing social and political conditions, but also to deep philosophical-moral doubts and reflection. The lives of such leaders were not black or white, but rather made up of multiple shades of gray. This was clearly the case of Chief Tasorentsi, who, from being a debt-peon and quasi-slave in his youth, went on to being a slave raider and trader; inspirer of an Ashaninka movement against white-mestizo rubber extractors and slave traffickers; paramount chief of a multiethnic, anticolonial, and anti-slavery uprising; enthusiastic preacher of an indigenized version of Seventh-Day Adventist doctrine; and charismatic people-gatherer whose world-transforming message and personal influence extended well beyond Peru’s frontiers.

Was there anything you discovered that moved you?

What moved me the most was the discovery of a song composed by Chief Tasorentsi as a means of transmitting his millenarian message. Colleague Jeremy Narby recorded the song in the 1980s from an Ashaninka friend who had learned it from Tasorentsi as a boy, and generously provided me with a copy. When I first heard the song, I was enthralled. I felt as if Chief Tasorentsi was trying to communicate with me across time. Narby had transcribed the lyrics but had not translate it. With the help of ethnomusicologists, linguists and anthropologists I finally managed to translate the song. Its message –that the creator god is coming to this earth to take his children to the waters of youth, where they will enjoy immortal life– expressed in evocative and melodious words the core of Ashaninka traditional religious beliefs.

What was the most difficult issue to research?

The most difficult part of my research was to find information on Chief Tasorentsi’s youth and old age. In those two periods, Chief Tasorentsi led a life away from the public spotlight. For this reason, there are few written documents for those years. It was thanks to interviews with Ashaninka elders related to Chief Tasorentsi and, more especially, with his youngest son that I was able to fill in those gaps. Oral histories thus became a crucial complement to archival materials.

What do you hope the book will do for readers?

With regard to non-indigenous readers, I hope that the book will allow them to get a glimpse of the richness of native Amazonian cultural practices and history, but also to realize the enormous odds that indigenous peoples have had to overcome in order to survive. It is my hope that greater knowledge of indigenous peoples’ past struggles will sensitize readers to support their present-day fight for their rights to life, land, and political autonomy. With regard to Ashaninka readers, I hope this book will recover a part of their history that has been largely forgotten; a history of courage against mighty odds in which not only leaders, but common men and women played a crucial part.

Did you have any difficulties in finishing the book and publishing it and if so, how did you overcome those?

No. Before I started to write the book, I signed a book contract with the University of Texas Press.

Do you have any online accounts where people can find more of your work?

Readers can find more about my work at: https://stri.si.edu/scientist/fernando-santos-granero

Author Biography

Fernando Santos-Granero

Social Anthropologist

Smithsonian Institute

Author of Slavery and Utopia: The Wars and Dreams of an Amazonian World Transformer, University of Texas Press, 2018.

https://stri.si.edu/scientist/fernando-santos-granero